Mark Eydelshteyn and I are in a car zooming down a mountain road on the first day of the Telluride Film Festival in Colorado. The young actor sits in front, while I’m in the back with two of the film’s publicists. His eyes light up as the driver informs him that his seat has a massager; he can’t believe such a thing exists. A few minutes later, he exclaims, “Guys, it really works! Let’s stop in a few minutes and change seats so you can try it out.”

About half an hour later, as we settle in for our conversation in a restaurant with a dramatic view of the valley below, his buoyant mood has changed somewhat. He looks at me and asks quietly, “In your eyes, who am I?”

Even stranger is what he says next: “I’m nothing.”

He may not be a recognizable face or name in the U.S., but Eydelshteyn is about to be far better known as one of the stars of Sean Baker’s sex-worker comedy-drama Anora, which won the Palme d’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival and is entering awards season trailing clouds of anticipation. So he’s not nothing. But the actor is still trying to figure out why anyone wants to talk to him. “I’m just some weird guy who somehow became a part of Sean Baker’s movie,” he says, baffled. He’s curious to know what interviewers think of him, he says, because then he might be able to give them the right answers. Or at least interesting ones.

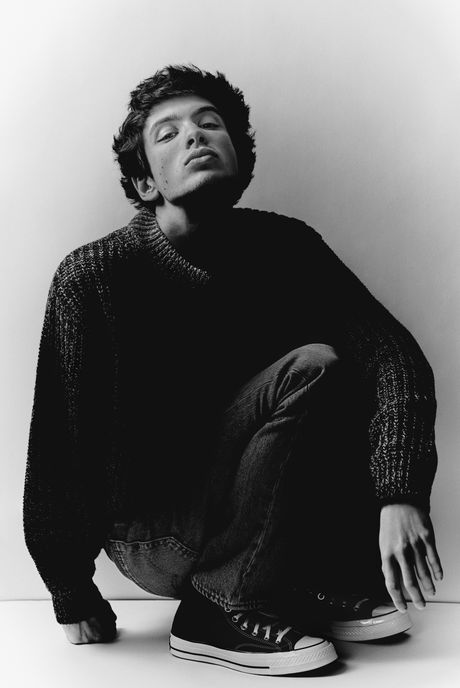

This is the Mark Eydelshteyn experience. His boyish charm, excitable nature, and youthful features make him seem even younger than his 22 years. A Variety article in May called him “the Russian Timothée Chalamet,” and Eydelshteyn noted that the comparison has been made in Russia as well. Maybe it’s just the hair. In person, he’s a lot less ethereal and aloof than Chalamet — more of a kid. That’s offset by an introversion, a self-reflection that feels older, wiser, and maybe a little more anxious. “He does have this very sensitive, deep side to him that I was lucky to be able to get to know better,” says Anora star Mikey Madison, who has the most scenes opposite Eydelshteyn in the film. “His English wasn’t as evolved as it is now when we were shooting. But we laughed a lot, hysterically. I knew immediately that we would have some kind of chemistry.”

In Anora, which is set and was filmed in New York City, Eydelshteyn plays Ivan, the impulsive, irresponsible son of a Russian oligarch who, after a few weeks of paying Madison’s stripper protagonist, Ani, to be his girlfriend, elopes with her. But all hell breaks loose when his disapproving parents sic their henchmen on the couple. That premise could easily fuel a far scarier movie, but Anora, for all its suspense and heartbreak, has a freewheeling levity that upends our expectations; it’s somewhere between a fairy tale gone horribly wrong and a screwball comedy. That may be why Cannes jury president Greta Gerwig likened the film to the works of Howard Hawks (Bringing Up Baby) and Ernst Lubitsch (Ninotchka) upon giving it the festival’s biggest prize.

Key to Anora’s remarkable tonal balance is Eydelshteyn’s performance. We can feel in our bones that none of Ivan’s promises will be fulfilled and that this hyperactive, hedonistic, pampered princeling will prove to be thoroughly unreliable. He also has just enough charisma, just enough sweetness, that we briefly find ourselves thinking and hoping that things might work out for Ani. “He put a lot of himself into the character — all the best parts, though,” says Madison. “The energy, his youthfulness, his quirks.” Eydelshteyn’s is not the film’s biggest performance, but it may, in its own sly way, be its most important — the one without which the whole enterprise would fall apart.

Eydelshteyn grew up in Nizhny Novgorod, an old and storied city on the Volga that he describes as “a stone jungle but very beautiful and dangerous.” (Trying to find its corollary in the U.S., we settle on San Francisco, even though he has never been to San Francisco and I’ve never been to Nizhny Novgorod.) His father worked as a sports journalist and his mother as a dialect coach. His road toward acting, he says, started off as punishment: Whenever he was caught misbehaving (usually for fighting with his younger brother), his mother made him memorize a passage from a book or a play. One of the first he committed to memory was the “If you want to know the truth, I’m a virgin” passage from J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. He says he can recite whole chapters of Alexander Pushkin’s 5,446-line verse-novel, Yevgeny Onegin, from memory. (He immediately starts doing it for me; I hear enough to believe him.) All these punishments paid off when it came time to think about a career. What can I do in this life to make the world a little bit kinder and brighter and sunnier? he wondered. Then he remembered how happy it made the people around him when he’d recite poems and novels and plays. Those feelings came rushing back, he says, at the film’s world premiere. “It may be the highest point of my happiness in my life when I sat in this hall in Cannes and people were laughing. I thought, Thank you, Mother, for this. I’m not mistaken.”

To help build the part of Ivan, Eydelshteyn recalled his experiences with a childhood friend in Nizhny Novgorod who was the son of an oligarch. (“Not one of the very popular and very, very rich ones,” he tells me. “We have lots of oligarchs in Russia.”) He remembers going to strip clubs and partying as a teen with his wealthy friend and the way the young man would always address everyone around him informally. (In Russian, as in many other languages, one addresses one’s elders and strangers one way and one’s friends another.) “Every zone is a safety zone for him because he knows that his father and his background can support him and protect him,” Eydelshteyn says. He also saw in his pal a frantic inability to be alone with himself, from which he drew Ivan’s constant sense of movement and almost pathological extroversion: “It’s scary to be alone with himself, so he has time for everybody.”

The Anora Reader

The actor learned about the importance of backstory and preparation at the prestigious Moscow Art Theatre School, the legendary dramatic academy founded in 1943 by Konstantin Stanislavski and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, from which he graduated last year. There, actors were taught to thoroughly explore their characters’ lives, to imagine and write down seemingly inconsequential details, all in an effort to have a full-bodied idea of a person before performing. The school was “bold and strict,” he says. He has a romantic fondness for the place. “The main thing they did,” he says of the school, “was to put inside me the idea that, Okay, you can be an actor. It’s not that difficult, really. You can play. You can analyze scripts. You can build a character. But you’re not allowed to be just an actor — you have to be more than an actor.” He pauses. “But what does it mean to be more than an actor? We had four years to think about it. I’m still thinking about it.”

Eydelshteyn recalls one of the first jobs he had for what he was told would be a film set in the waning days of the USSR, when one could only illegally procure western rock music. He was to play a black marketer selling American music. He did his research and even consulted with his father about what kind of music would be popular at the time. During the shoot, he went up to the director to show him some of the research and backstory he had created for his character — only to get laughed at. Turns out the shoot was an ad for a vinyl-record store. “It was very funny,” he now says. “But in that moment, it was very sad.”

Also in that moment, he became determined to make real films — serious ones that allowed him to experiment. Since then, Eydelshteyn has starred in a number of productions in Russia, including 2022’s The Land of Sasha, an independent romantic drama that didn’t make much money at home but played at the Berlin International Film Festival, and the sci-fi adventure Guest From the Future. It was his co-star in the latter project, Yura Borisov, who recommended that he try out for Anora. Borisov had already been cast as Igor, one of the overwhelmed goons tasked with trying to convince Ani to annul her marriage to Ivan.

Determined to build a character before recording his self-audition video for the film, Eydelshteyn felt that Ivan would have extremely expensive clothes and accessories — Gucci glasses and Dior shirts, say — that had been dirtied up. But the actor couldn’t afford any such outfits, and he certainly couldn’t afford to ruin them. So he went with what he felt was the only other option: He did his audition naked in bed. A risky choice, perhaps, but the actor blocked out any notions that Baker might be offended or not respond. “I can’t imagine a situation that Sean would just say, ‘What? What? I will cancel him! Why do I have to, during an audition, see the ass of this guy?,’ and break his phone.” He was right. “It just blew us away — not only his boldness, but also he was truly funny and down to earth. We couldn’t consider anyone else for the role,” says Baker.

For all his confidence and energy, Eydelshteyn was nervous on set in his early days. His first scene — which wound up getting cut from the film — involved Ivan sitting quietly waiting for Ani while she was standing in a cryotherapy chamber. Eydelshteyn says Baker told him before rolling that he could smoke a vape pen. The actor looked at the vape and thought, You are my closest friend here. I will work with you. We are going through this journey together. You will help me, I hope. Thank you, man. And so he started vaping incessantly, which became a trademark of his character.

He was also quite anxious about his first sex scene with Madison. Baker closed the set and told them that the crew would be very careful in how they shot the scene to avoid any sense of exploitation. For Eydelshteyn, this had the opposite effect. “With every word, this uncomfortable feeling of shyness was just racing, racing, racing inside of me.” But that tension resulted in one of his more inspired improvisations: a sudden and joyous backflip in which he would, in one simultaneous action, throw off his clothes to reveal his penis — a moment of unexpected hilarity. This also set his co-star immediately at ease. “This was the first sex scene I’d ever done,” says Madison. “I had no idea what it would be like. He was so nervous, but he felt the need to make sure I wasn’t nervous. I found that very giving of him.” Baker encouraged improvisation for the English-speaking scenes more generally too: “A lot of the best lines in the film are ones Mark came up with.”

Anora will surely open more doors for Eydelshteyn abroad, and he’s studying English, trying to improve his accent, as he’d like to do more parts in international pictures, though he’s aware of Russia’s tarnished reputation as a result of the war in Ukraine. He chooses his words carefully when talking about Russia and recognizes that certain areas of conversation might be, as he puts it, “dangerous.”

His parents have yet to see the film. They know of it, obviously, and they’re proud of the awards it has won. He has told them it’s basically a fairy tale and he plays a modern prince. (“I’m not lying,” he adds.) And despite his mother having spent her whole career working with actors, Eydelshteyn is scared that his parents will not be able to accept him “doing bad things, drugs, alcohol, and saying bad words. I will have to explain to them, ‘It’s not your son. You’re not oligarchs. It’s just a role.’” Then he stops again and cracks a huge smile. “It’s not me, but I honestly love this character. So yes, it’s your son, Mother! And it’s your son, Father! Thank you.”

More on ‘Anora’

- Awards Season Starts … Now!

- Anora’s Ending Is No Fairy Tale

- Why Did Sean Baker Avoid Politics in His Films Until Anora?